It’s a Writer’s Market

Digital platforms have emerged to serve midlist authors.

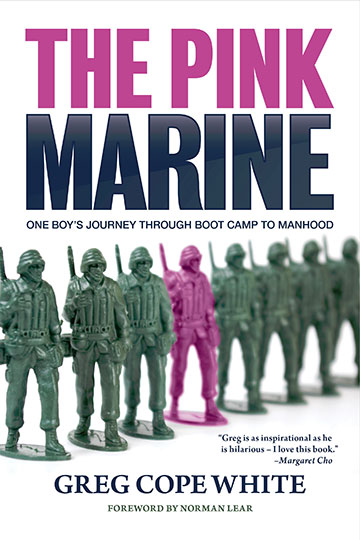

For Greg White, the last straw came when his publisher forgot to ship copies of his book to the launch party last October. It was just one in a series of lost marketing opportunities, says White, co-host of the Food Network show Unique Sweets. So he decided to take his book back. After getting his contract canceled, he turned to the editorial marketplace Reedsy to redesign The Pink Marine, his memoir about life as a gay serviceman. The author, who lives in Santa Monica, Calif., formed his own imprint, AboutFace Books, and cut a distribution deal with Ingram Content Group. “Five years ago, self-publishing was a scar,” White says. “Now it’s a tattoo.”

A new generation of online editorial services and self-publishing platforms is fueling that change in perception. The upstarts offer skills and services that used to be available only through traditional publishing, plus favorable royalty splits. They also allow authors to retain the copyright to their work. The array of offerings is spurring some writers to leave their publishing houses—particularly midlist authors whose books receive scant marketing support. Some are also using the new services to put out e-book versions of their out-of-print titles.

Janice Graham used Amazon.com’s Kindle Direct Publishing platform to release digital versions of her five novels, including 1998’s Firebird, a New York Times best-seller. For a novel in progress, she hired an editor through Reedsy and plans to self-publish unless a publisher offers her a good deal. “I’m not so interested in the prestige of being published by a traditional publisher at this point,” says Graham, who lives in Florence, Italy. “What I’m interested in is maximizing sales.”

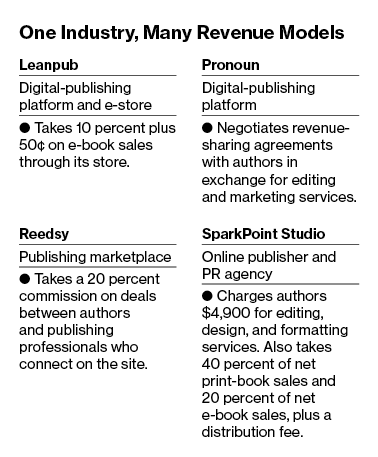

Reedsy is a community of about 450 handpicked publishing professionals available for hire. The two-year-old London-based company offers software that allows authors to collaborate with editors without having to e-mail manuscripts back and forth. Reedsy co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Emmanuel Nataf says he had an epiphany when he got his first Amazon Kindle e-reader: “The barriers to publishing had been removed.”

Self-published titles account for almost half of all e-book purchases in Amazon’s Kindle store, while e-books from the five largest publishers represent just a quarter, according to the website AuthorEarnings. Still, demand for digital titles has weakened somewhat: E-book purchases—which average $4.95, compared with about $15 for trade paperbacks—peaked in 2014, when they made up 36 percent of the publishing market. They’ve since declined, as consumers with digital fatigue return to print, according to Peter Hildick-Smith, founder of Codex-Group, a consulting firm in New York City. “I believe the market is now in more of a steady state,” he says.

To compete against traditional publishers, self-publishing platforms target specific niches and offer authors terms their old-line competitors can’t match. Pronoun, formed last year by a merger of three companies, is free for authors to use, distributes their e-books to Amazon and other online retailers, and doesn’t take a cut of their sales. (Traditional publishers typically keep 75 percent of an e-book’s net profit.) Pronoun only negotiates revenue-sharing agreements with authors who use its editorial and marketing support. “Where publishers make guesses, we run the numbers,” says Josh Brody, CEO of Pronoun, based in New York City. “We apply advanced data science and analytics to help authors price their book competitively, get it into retailer categories that provide the highest visibility, and tag their books so they show up in the most popular and relevant reader searches.” (Pronoun was acquired by Macmillan Publishers for an undisclosed sum after this article went to press.)

Leanpub gives technology writers the ability to publish in-progress works. That way, they get feedback from readers and earn royalties while they’re writing. The company, in Victoria, B.C., takes a 10 percent cut plus 50¢ on each sale through its online store. “If you’re writing about an area that changes quickly, your only hope of being relevant is to publish quickly,” says Leanpub co-founder and author Peter Armstrong.

Meredith Wild, an author of erotic fiction based in Destin, Fla., snagged a $6.25 million advance from Grand Central Publishing’s Forever imprint last year for five novels—four of which she’d already self-published. Forever had sold about 500,000 copies of the books through January, compared with 1.5 million Wild sold before the deal through her own aggressive marketing. That differential is one reason she’s gone back to publishing her work—along with that of other writers in the genre—under the imprint Waterhouse Press, which she started in 2014. “It’s more of a personal investment of time and money to have my own team,” she says, “but at the end of the day, I like being able to call my own shots.”

Self-publishing isn’t for everyone. “It’s definitely like running your own business, and not everyone is up for that,” says the author, who uses the e-book creation software Vellum. “For those who are, it’s a great way to publish on your own terms.”

The bottom line: A number of self-publishing platforms are wooing established authors by rewriting the industry’s contract terms.

0 Comments